Spassky at a Safe Distance, Issue 18

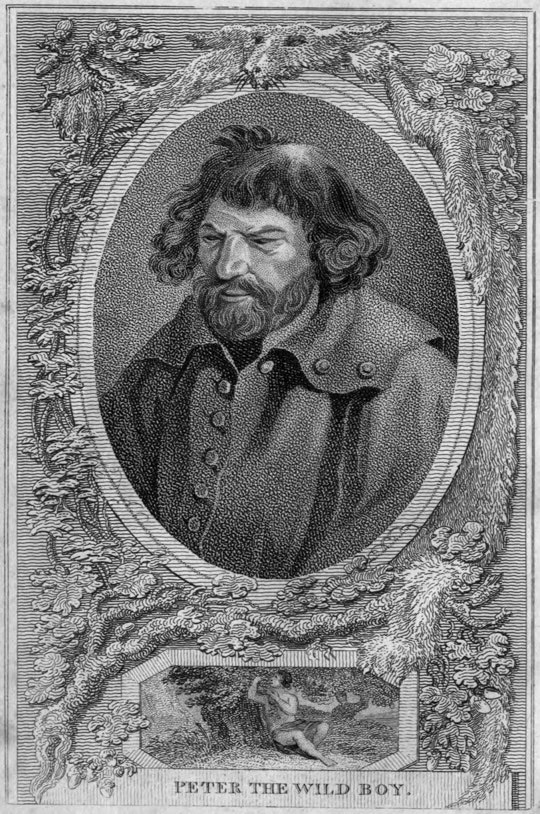

“Peter the Wild Boy”

1: Introduction

2: Spassky’s Assorted Somethings

3: Bonus + Short Story of the Week

1

I’ve tried to tell Peter’s story, which is a bittersweet story, with as light a tone as I could, because bittersweet stories are best if in greater part sweet. But I’m sure that you will want to balance this sugary frame of the story with the bitter variety, so I’ve linked an article from the BBC – which certainly does the job – as a sort of Bonus-Bonus.

2

It was in 1725, It was in a forest in Germany, and It was also on a hunting trip, that King George I discovered a wild Germboy (he wasn’t quite old enough to be a German). The boy walked on all fours, he growled and barked and did not wear clothes. On the whole, he presented all evidence against being any good to eat, and showed altogether less promise as a Trophy of the Hunt. He was therefore – mercifully – spared.

But with the question of “Fire at will?” answered, there still remained the one about What the Devil To Do With the Boy. After a brief conference, the party concluded three things.

1) That the Germboy was probably raised by wolves, or bears, or some other disreputable sort.

2) That he was unlikely to live a long or happy life if left as he was.

3) That he would be a wonderful addition to the royal family of the British Empire.

The boy (who they for some reason named Peter) was immediately shipped off to England, to live in Kensington Palace.

There he was instructed in Speaking, Walking Upon Two Legs, and Wearing Clothes. Peter made great strides in Walking, pulled himself right up by his bootstraps in Clothes-Wearing, but was left dumbfounded, I should say speechless, in Speaking. It is documented, however, that he understood what others said to him (and, as for the speaking, he did eventually – very eventually – learn to say “Peter”, and “King George”, which I think is very sweet).

Peter (the Wild Boy, as the press and print – lovingly – called him) became an immediate celebrity (indeed, how can you take a poo on the imperial throne and not?). But Peter was not nearly as famous around the Common People, or even the League of Royal Janitors, as he was in the circles of the Foremen of the Enlightenment – philosophers, scientists, brainy birds of that plumage.

“People have souls” most philosophers agreed on that; “People are not animals because people have souls and animals do not.” most of them agreed on that too; but where they all got to scratching their powdered wigs was at the question “So what about Peter?”. Peter was human (or a fair enough imitation of one), yet could not speak, or walk, and behaved a hair more animalistically than the margin of error allowed for (even if adjusted to French standards). Did he have a soul? Do we have souls? Were humans once soulless animals, too (Darwin was about 100 years unborn)?

(One of these philosophers, or at any rate, one who philosophised on Peter and what he meant, was Daniel – [profanity of choice] – Dafoe: the guy who wrote Robinson Crusoe. I have linked his book about Peter, “Mere Nature Delineated”, as this Issue’s Bonus – a digitalised first edition!)

Peter upset the view of humanity to such a pitch that Carl von Linné – the father of nomenclature – had to divide humans into two categories, “Homosapiens”, and “Peter”. (okay, it was a bit more sciency than that; “Peter.” became Juvenis hanoveranus, “The Hanoverian Youth”. Peter was found in Hanover, making him “Hanovarian”).

As with many Londoners, after a few months in the city, Peter became restless, listless, and longed to run naked in a forest very far away.

He was sent to live on a farm in Hertfordshire, where he could do just about whatever he wanted; this involved a lot of running around in the woods, and – once too occasionally – not coming back. That “once” which was “too occasionally” made the farm-people fit him with a collar, reading “Peter the Wild Man of Hanover. Whoever will bring him to Mr. Fenn at Berkhamsted shall be paid for their trouble.”

And that’s pretty much it. Peter enjoyed life on the farm and lived into his seventies (in the 1780s, remember; that’s like living two-hundred and a half today). [The hunting party guessed he was at least ten, at most fourteen, in 1725].

It is said Peter’s favourite activities were star-gazing and fire-stove-gazing; he picked acorns in autumn, like he did in That Forest in Germany; he also liked gin, and singing, and singing while drunk on gin.

Peter died in 1785, and the farm-hands collected their wages to give him a headstone; it stands til this day, always in the company of a great many flowers.

3

Bonus: A 300 Year Old Copy of Daniel Dafoe’s ”Mere Nature Delineated”

Bonus-Bonus: The Bitter Part

Story of the Week: (Completely Unrelated) ”His Wife’s Deceased Sister” (Frank Stockton, 1884)

Your faithful servant,