Spassky at a Safe Distance, Issue 15

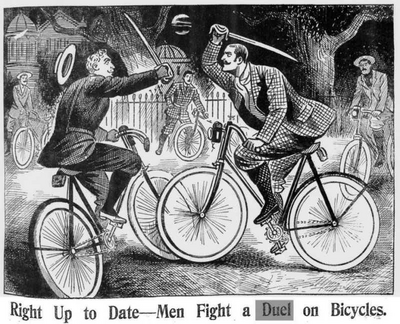

“Duels Three – Lackadaydee?”

1: Introduction

2: Spassky’s Assorted Somethings

3: Bonus + Short Story of the Week

1

With pistol and sword

Were the violently bored

(‘Til George Who Came Fourth) used to fight,

Whenever a question

Of courageous aggression

Was raised ‘tween two parties with spite;

But spelling and grammar,

An etiquetteual stammer,

Could also avengeance excite,

(However ‘twas rare

This hom’cidal affair

Would end with a “Snuff-o’-the-Light”)!

Three duels (the greatest that history’s seen)

You will learn all about in this Spassky (fifteen)!

2

Lady Almeria Braddock vs Mrs.Elphinstone (1792)

It wasn’t High Noon (it was probably around Afternoon Tea Time) when Mrs. Elphinstone paid a compliment she would – almost – pay for with her thyroid cartilage (and every estimable thing above it). It went something like, “Lady Almeria Braddock, you who have so kindly invited me to Afternoon Tea at an hour which probably is not High Noon, I wish to compliment you on your appearance – you are remarkably well-preserved for someone so old!”

“You will certainly be busy at the Retirement Club!”, “You make arthritis look fashionable!”, and “The mortician will find you very attractive by and by!” were surely sentences also mobilised in this Operation: Flattery.

Unfortunately, the operation was met with a counter-offensive:

The Conflict In Lady Almeria Braddock’s Living Room:

Date: Probably Around Afternoon Tea Time – Probably Around Afternoon Tea Time and one minute.

Belligerents: A disgruntled Lady Almeria Braddock and the parts of Mrs.Elphinstone not hidden behind a large drawer.

Territorial Changes: An Upset Tea-Table and confectionary laying in places they could not have reached by natural means.

Strength: Braddock: A Tea-Set. Elphinstone: Appeals to a higher power.

Casualties: Lady Braddock’s temper, seven sets of china, an ornamental vase, approx. nine litres of tea, cookies-and-cream in uncountable numbers, hope of escape and Elphinstone’s religious convictions.

(Lady Braddock would have probably been more receptive to these compliments were she fifty years older, and not recently turned thirty)

Despite condolences, and assurances on the part of Mrs.Elphinstone that she was a sorry and failed comedian who did not mean anything she had said, the Lady told the Mrs. that her anger would only be satisfied under one, or both, of two conditions:

1) That she restors her honour by beating Mrs.Elphinstone in a duel.

2) That Mrs.Elphinstone’s head be severed and sent to Bradock in a box with a bow on it.

They started off with pistols.

Mrs.Elphinstone shot first, mortally wounding Lady Braddock’s hat. The Lady, doubtless disoriented by this terrible bereavement, missed the Mrs. entirely with her shot.

They decided to settle the matter with swords instead. The Lady was probably trained in this weapon, for she almost amputated Mrs.Elphinstone’s right arm. Mrs.Elphinstone conceded the duel after this, probably because she was right-handed.

Worse still for Elphinstone, she had to write a letter of apology, regarding her observations of the honourable Lady’s aspect, for Braddock to pardon her. What would have happened otherwise I don’t know, because the apology was written and the dispute was settled.

(I guess this is why you should never ask a lady her age)

John Randolph vs Henry Clay (1826)

Randolph and Clay had two things in common:

a) Both were venerable U.S senators (who nearly secured presidencies).

b) Their favourite rhetorical device was the gun.

Randolph and Clay had done a good deal of mudslinging almost since learning of each other’s existence, but it was in 1826 (when Clay was Secretary of State) that they added the prefix “mortal” to their mutual pet-name of “enemy”. It was during a debate in the senate (I guess, a disagreement of whether the Triangle Trade should be Equilateral or Right-angled) that Randolph called Clay a “black-leg” (fraud). This was a very populated senate – and a very bad place to have one’s leg so tastelessly criticised – so to defend his honour, Clay challenged Randolph to a duel. And to defend his honour, Randolph accepted.

Then commenced one of the greatest Trash-Talking campaigns of the 19th century.

Randolph boasted in public, in newspapers, in legislative procedures that would determine the future of America, that he would beat Clay with his first bullet, that he would do it in the time it takes to collect the mail, that he would wake up just before it and go to bed after it, and that he would shoot Clay in the shoulder, as to not embarrass him by beating him in that disgraceful way and killing him (or his bullet by dishonouring itself in any section of Clay’s body containing more Clay).

At sundown on the 8th of April – having spent the night before reading poetry – Randolph (in an oversized morning robe) met Clay in some forest in Virginia to do war.

With their preferred rhetorical devices set to discover fire, they lined up, marched thirty paces apart and – forming the protocol by which the legends of the Wild West would be made – turned and fired.

When the smoke cleared (pistols were like miniature muskets back then) it was clear no-one had died – no-one they were aiming at anyway.

They had agreed on a one-round duel, but with this result reflecting badly on their rhetorical skills, they had another go.

“Primed and ready”, they lined up, marched thirty paces apart and – each trying to beat the other in the speed of the turn and the draw – fired.

Clay’s shot trimmed Randolph’s robe, and Randolph’s shot, in the very deadliest case, offended the troposphere.

Clay called off the duel after that (his honour restored or leaking out of his pants), and Randolph greeted him by saying, “Mr.Clay, you owe me a new coat.”

No accounts confirm whether this coat was purchased, but we do know that Clay and Randolph went on to become good friends and reached prominent political positions (I can’t say whether this was for better or worse, though).

And all parties concerned lived happily ever after.

General Francois Fournier vs General Pierre Dupont (1794 – 1813)

General Dupont was charged to deliver a message to Fournier, in which lay a positively scindering telling-off addressed to “the worst subject of the Grand Armée [the Napoleon Army]”.

Quite understandably, Fournier was upset after reading the message. I fear he was in such a bad mood that he confused his proverbs, mixing up “Don’t shoot the messenger” with “A good Frenchman is a dead Frenchman”. He challenged Dupont to a duel (in Fr-nch fashion) with rapiers.

It was a very short duel which Founrier – in convincing fashion – lost.

Undeterred however he proposed another duel, this time with pistols. Fournier had more luck in this weapon, and Dupont more Leak (which is to say, he was shot, and I take liberty to suggest that wound leaked).

The score being even, (and the duellers too punctured to continue fighting), Founrier and Dupont drew up a contract, the terms of their private war (so they could pick up where they left off). It said that they would duel if ever within 100 miles of each other, that if one was unable to travel the other would come to him, and that nothing – except death – was a good enough excuse to breach the contract.

They would follow these terms for nineteen years, fighting with lances, and pistols, and rapiers and sabres and fists, on horse-back, on foot, and very likely, in an amorphous mass on Floor.

All this without a decisive result.

It was in 1813, after a duel in which Fournier was nearly decapitated, that Dupont decided to announce he was engaged to be married. He told Fournier that the fighting had to end, for he could not fulfil his duties as a Lawful Husband to Have and Hold From This Day Forward, For Better, For Worse, For Richer, For Poorer, In Sickness and Health Until Death Do Us Part, and a Murderous Supreme-Arch-Rival (of the same convictions) silmontaniously.

The matter, seventeenth and for all, had to be settled; it would be a duel of pistols in a nearby forest.

There wasn’t much form to the battle: they got their guns and ran away from each other (to hunt the other stealthily when out of sight) – a sort of cat-and-mouse chase, but with only cats.

Eventually they came upon each other, and hid themselves straightaway behind two – quite separate – trees. Owing to the guns of that time being a one-shot-and-a-million-years-reloading affair, whoever shot first would have to hit their target, or else find themselves in a very embarrassing situation. Dupont, therefore, ripped off a bit of clothing, and dangled it in Founier’s Line of Sight, making it look as though some vulnerable section of him was peeking around the tree-trunk – all to induce Founrier to–Bang!

And a Bang! it was, sure enough. Trigger-happy Fournier fell for the trap, and Dupont charged him, threatening Fournier’s cerebellum while the poor man was still 1/1000th through his re-loading.

Fortunately, Fournier accepted defeat without argument, and heard no retort (report, rather [report of a pistol, that is]).

And then there was peace.

3

Bonus: A Collection of Victorian Magazines

Story of the Week: The Duel (Guy de Maupassant, 1883)